How Often Should A Customer See Your Ad? Here’s One Way.

Before the world caught the Covid cold, my rubber arms were whipped into a frenzy and quickly bent when two close mates signed up to do an Ironman. A gruelling event, a full Ironman involves doing a 4km swim, jumping out of the water, throwing your leg over a bicycle and riding for 180km cycle, before getting into some runners and finishing off with a marathon – 42 km of torturous running.

When the 3 of us registered, and the actual event still 9 months away, I knew that if I was going to do this, I was going to do it once – and I wanted to do it right. I put inside my head, an ambitious goal that I could set out to achieve.

To complete the Ironman in under 12 hours.

To do all 3 stages under that time certainly wouldn’t be a walk in the park – and breaking each segment of the event down I started to think whether I could actually achieve such a feat given I had never completed any kind of triathlon before, my arse sank like an anchor whenever I went swimming, and my most recent athletic endeavours seemed to be lifting jars at the pub.

Needless, the goal had been set. As excitement quickly faded, a question lingered in my head that I couldn’t shake – how much training could get me to my goal?

The other lads had been pondering the same thoughts around training, and after numerous conversations, debates, and beers between the three of us, we each set out on our journey.

Ultimately, the 3 of us completing the event each chose a different training method. One of us bought a training program from an online Ironman coach, one of us joined a triathlon club, and one of us winged it. Three different approaches, three different methods.

Frequency is not black and white

Marketing campaigns live and die by the numbers. I am of the church that believes marketing falls more in the latter – rather than the former – of the phrase ‘marketing is an art & science’.

Marketing no longer inhabits the world of Don Draper – if it ever did – where a flashy presentation and smooth talking suit could get you through the meeting and to the long lunch.

When marketers look at their campaigns, when agencies optimise campaigns, and when bean counters decide what budgets to hand their marketing teams next year – there’s a huge array of metrics, and numbers at their disposal.

One of the most common numbers thrown into the review of any campaign is that of frequency. How often has an advertisement been seen by the audience?

If a campaign has 1,000,000 impressions (amount of times an ad is served), and the campaign’s reach (the amount of people that see the ad) is 500,000 – then you have a frequency of 2. In this example, on average, anyone who has seen the advertisement, has seen it twice.

Frequency is never a primary objective of a campaign – I’ve never received a brief from a client that asks for their campaign to have a frequency of at least 3.7. Frequency is one of the pieces that helps you reach your objective.

When it comes to frequency – much like Ironman training – there are different methods, and different approaches.

No approach is better or worse than any other. They’re just… different.

Effective Frequency

‘Effective frequency’ as a concept was probably first broached at a listening party of Pink Floyd’s own concept album ‘Dark Side of the Moon’ in the mid 70’s. Effective frequency proposes that there is an optimal number of times an advertisement is seen at which point the effect of the ad is maximised, and at any point thereafter, the effect of said advertisement receives diminishing returns.

A common debate amongst marketers is whether campaigns should be focused on ‘reach’ – driving memorable impact on your customer, even after one exposure. Alternatively, there is a school that believes campaigns should focus on ‘frequency’, ads have little impact on the consumer, and need to be seen multiple times to have any impact.

For example, if you are a new brand in the market, you have low market share and need to make a dent – your required frequency needs to be much higher than if you’re an established brand. New brands need to get in front of their audience more, and more, and more – to build up their brand recall, and brand recognition in the eyes of their consumer.

Similarly, if your proposition is simple, doesn’t need much explaining, and you have an ‘always on’ or continuous media campaign, your frequency won’t need to be as high because the message will land quicker, or the audience will see you for longer.

One model that brands can use to determine what frequency a campaign should be hitting in order to deliver effective frequency, is the ‘Ostrow Model’; devised by Joseph of the same name, in 1982 which uses a number of factors to help determine whether your campaign should increase, or decrease its frequency.

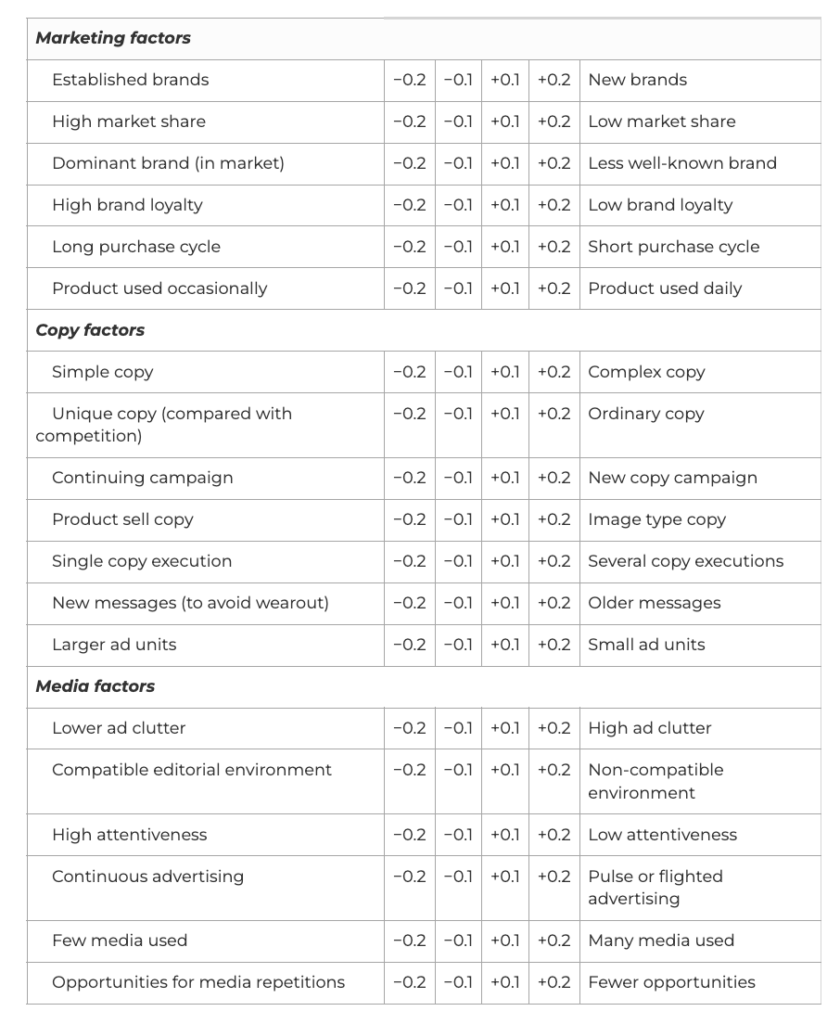

Ostrow’s model of effective frequency is based off 3 x factors that any brand and their campaigns fall into:

- Marketing Factors

- Copy Factors

- Media Factors

Ostrow’s 3 Factors

Ostrow determined 3 attributes in order to help determine effective frequency, and within each attribute, there is a 4-point axis, for example “very low (1) > low (2) > high (3) > very high (4) that brands and their ads will lie on.

Marketing Factors

These factors relate to where the brand falls in relation to its market. They include factors such as a brand’s current market share (high v low), how established a brand is (long-standing v startup), or even product usage (occasional v daily).

Copy Factors

These factors relate to the brand’s advertisement, in particular the copy (i.e. words and messaging). For example, you would measure the complexity of your messaging (simple proposition v complex proposition), or even how many executions of a particular advertisement you would have (multiple copy executions v single copy execution).

Media Factors

Finally, these factors are determined by the media that the advertisement is being published in. For example, how much ad ‘clutter’ (high v low) will your ad have to compete with, or how long your campaign and advertisement will be in market for (continuous v one off blitz)

Calculating estimated effective frequency

Ostrow’s model of effective frequency determines that any advertisement should start with a frequency baseline level of three (3) exposures. Brands can then use a variety of factors in the table below – pending where they fall on the axis and scale – to add, or subtract points to this baseline number.

For example, If you are a startup brand, you will add +0.2 to your baseline of 3, giving you an effective frequency score of 3.2, whereas if you’re an established brand in market of say 20 years, you can subtract -0.2 points from your baseline to give you an effective frequency score of 2.8.

To get your estimated effective frequency number using Ostrow’s model, you would then go through every factor adding or subtracting points, until you reach the bottom of the table, and tally the points together – giving you effective frequency.

Drawbacks

Much has changed in music since Pink Floyd released their concept album, and similarly, much has changed in marketing since Ostrow released his concept for effective frequency. The channel mix for brands these days is much more diluted and populated than it was back in 1982, but debate around frequency rages on.

There isn’t an exact science to determine effective frequency. All we have are concepts. Science is merely a hypothesis until it’s disproved, and as marketing is both an art and a science, frequency, and the methods to determine frequency should be no different.

For the Ironman, between 3 of us, there were 3 different goals, and 3 different training methods to get us there. For marketing campaigns – don’t get bogged down in trying to find the ‘right’ method to determine frequency. Focus on your overarching campaign goal, and let frequency help get you there.

Let's start a conversation! Contact us now

Check us out on our socials!